Finding God in a Pagan Practice

FINDING GOD IN A PAGAN PRACTICE:

Stretching Sacred Happenings

BY AK CAROLL

On a Sunday in November, less than three months after I move to California, two women ask if I want to tag along for a yoga class after church. People say things like that in California: “Yoga after church.”

In other parts of the country, yoga is seen as apostasy—twisting and folding into ancient shapes with Sanskrit names that honor pagan gods or invite untested spirits. I’ve watched evangelicals share online articles that denounce the dangers of yoga or the perils of meditation, but not here in Berkeley. Out on the left coast, we’re a little more flexible.

How hard could it be? I think. I can stretch for an hour.

Turns out yoga does not equal stretching.

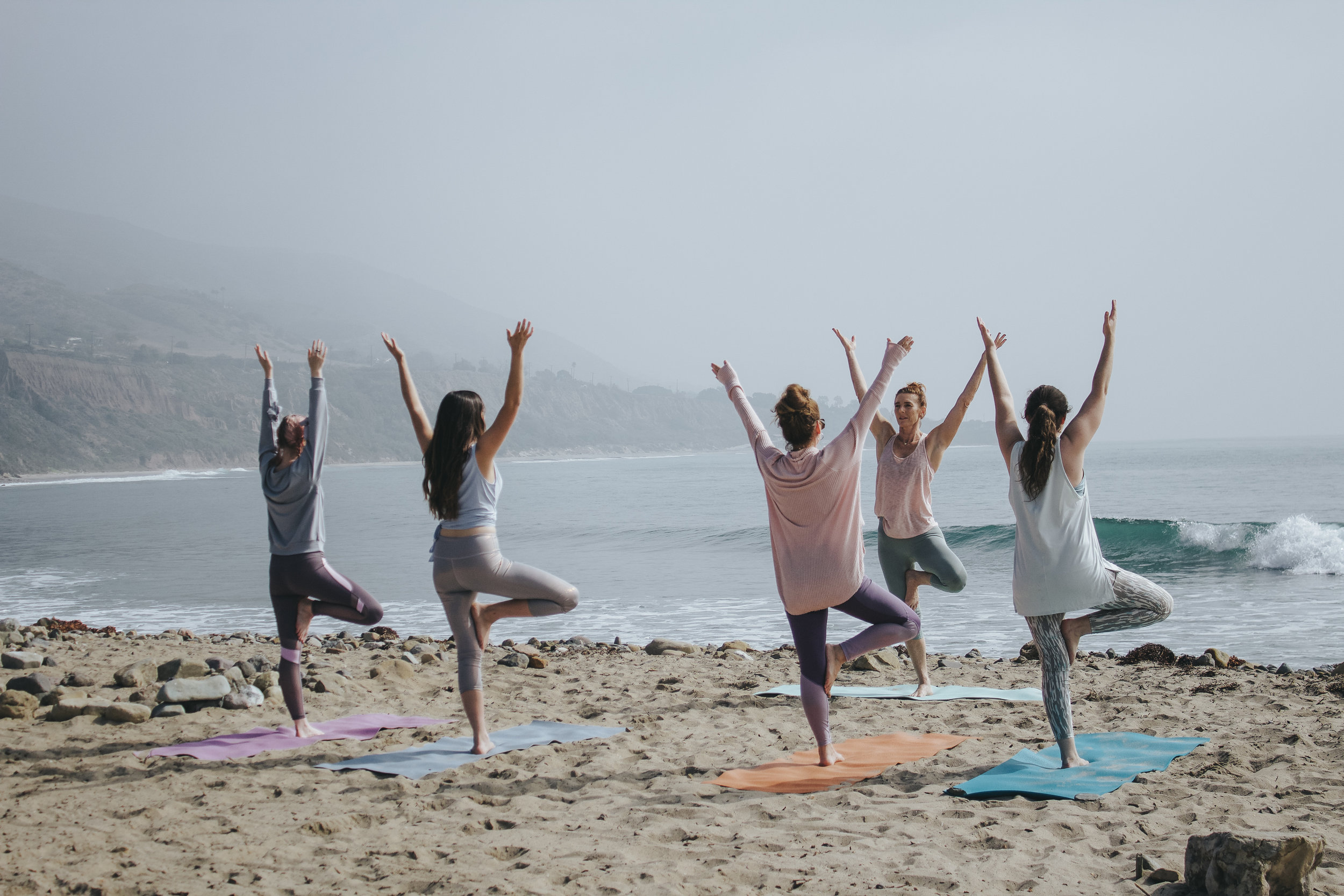

I enter a room full of humans splayed out on colorful strips of spongy rubber. I hear one exhale a moan and see another on her back with her legs spread open, hands on her feet. There’s a bench in the front with a small stack of books and a large golden bowl that sits on a pillow. They are tools of the trade, but they seem out of place. I don’t see the connection between body and mind. I’d never been told that a bowl could sing.

I feel a bit out of place as I pick up a green mat and find a spot in the back, near a stack of foam blocks. The class quiets down as the instructor walks forward, the sleeves of her sweater falling softly behind.

My first class starts like most classes — in child’s pose. Knees to the mat, sit bones resting on heels, belly folded to thighs like a compressed spring. This first pose is supposed to be passive and familiar, a place of resting and ease, but during my first foray into yoga, everything feels foreign.

I’m told to find and focus on my breath like it’s gone missing. I think that’s sort of funny until I realize that it’s true — that I spend most of my day only half in my body and that the depths of my lungs are rarely put to use.

In the Jewish and Christian Scriptures, the Spirit of God is characterized as a wind or breath, as the ruach within that bears witness alongside the nefesh of life, the breath of the human. These two words delineate in Hebrew what we blend in English, the breath where all of our power comes from, all of our life on all of its levels.

“Yoga is not about doing it right,” says the instructor. Every other instructor I will ever have will say the same thing, but my first time on a mat, getting it right is all I can think about. I don’t know any of the poses or how they connect. I’m not sure what a flow is, but I can tell that I’m not in one. I spend most of my time watching other students bend and glide and cycle with ease as I fake my way through. My arms flail, my hips are tight, and my legs are shaky. I make it through class wondering if I’ve actually done yoga at all.

For years after that first class, yoga will be something that I do randomly to relax or socially to connect. I’ll go to yoga the way that some people go to church — when I’m invited or when I feel like it, but only if it fits into my life. It will be a persona I try on, but not a practice that I own.

Then I will meet a man who catches my curiosity and shows me by example what embodied mindfulness looks like. He will talk about yoga in passing, but never with pressure, never as a proselyte. We will go for long quiet walks and take slow measured breaths. I will slip back into the studio and then one day I will find myself stretched into spinal twists and locked in ankle binds. I will marvel at the things that my body can do, and I will start seeing that yoga is more about living than stretching.

Each class will begin like that first class in Berkeley, with us all on our knees, arms stretched out straight. I’ll be told that child’s pose is always available as if it is never too late to go back to the start. I will hear this class after class, but at first, I will not understand.

At first, I will see it as a sign of weakness when other members of a class break from challenging poses and sink to their knees; when they listen to their bodies say “that was enough” and acknowledge their own limitations. My fear of failure will rise to the surface and I will believe I am better for sticking it out. I will push my limits and pay for it later rather than sit myself down and risk falling behind. I will see that sort of sitting as a form of surrender until I see it as strength, as grace.

I will redefine success and sanctification as I experience the power that comes from knowing and owning both your capacities and your boundaries, your abilities, and your limitations. Eventually, I will sink into child’s pose and it will be home, and I will realize that it is as much about being as breathing.

I will find satisfaction in the familiar flow from Warrior One to Warrior Two, and the poses that follow, in seeing what my body is up for each time I come to the mat and giving it grace when that’s less and not more. I will learn to feel when my spirit can stretch, and I will learn when it’s time to step down. This will teach me to tap into the nefesh of my soul and to differentiate it from God’s ruach within me.

I will marvel at classmates whose practices are deep and stop judging myself so harshly against them. This will teach me to be kinder to myself and to others, not just on the mat or in the studio, but on the street and in my office.

I will learn to see new poses as invitations to try and fail and then try again. I will fall and fail many times. But also, I will start to surprise myself. I will make shapes and hold poses I did not think I could, not because I try just a little bit harder, but because I stop trying so hard. Because I let it happen or not happen and I try not to judge either outcome as better or worse.

This is actually the hardest work that I will do, both in yoga and in life. Accepting that no one is doing it perfectly, that we are all trying our best and finding our edges, and that pushing past them requires as much gentleness and grace as it does strength and power.

I will learn what it feels like to be fully present in a pose, my muscles lit up, the tension running straight from my toe pads to the crown of my head. And I will learn what it feels like to fake it and hope no one sees, as I put my arms and legs where I think they belong without any real notion of power or strength. I will see this translate into my work and relationships as I begin to notice the occasions when I really show up with my whole self for someone and when I split my attention or act without purpose.

I will look forward to shavasna, the death at the end of each practice. I will work hard so that I can rest deeply, and I will come to realize that when death does come, I want to have lived my life the way that I practice yoga, with purpose and strength, humility and grace, able to acknowledge my own limitations and to discern when it is time to rest and when it is time to work.

I lay back on my mat at the end of that first class and stare at the globe-shaped lamps that hang from the ceiling. I glance right and then left at the bodies beside me, laid out like sunbathers on a beach or corpses in a morgue, eyes closed, lips parted. I wonder if maybe I missed something important, if maybe the magic of yoga had not yet settled in.

The instructor tells us to stay in shavasna for as long as we need and I don’t know what this means or why I would need to stay here just laying on my back, but I do anyhow.

Sometimes this is how mystery happens. Sometimes you stumble upon the sacred when you think you’re looking for something quite different. Sometimes you enter a space that is subtly solemn and you don’t go back for months or years, but then when you return you know you must stay. Sometimes you have to start by doing, by following a practice you don’t understand and moving through rhythms you can’t yet keep with the hope that the rest will come later. Sometimes you just have to start with yourself, to be in your body and work the truth through your muscles before it can seep to your soul.